A couple of weeks ago, in a terrible accident, the Bayesian, an imposing 184-foot-long sailing yacht topped by a 237-foot mast (one of the tallest in the world), sank, as the result of a sudden and violent storm off the coast of Sicily.

The Bayesian was owned by “the Bill Gates of Britain,” Mike Lynch.

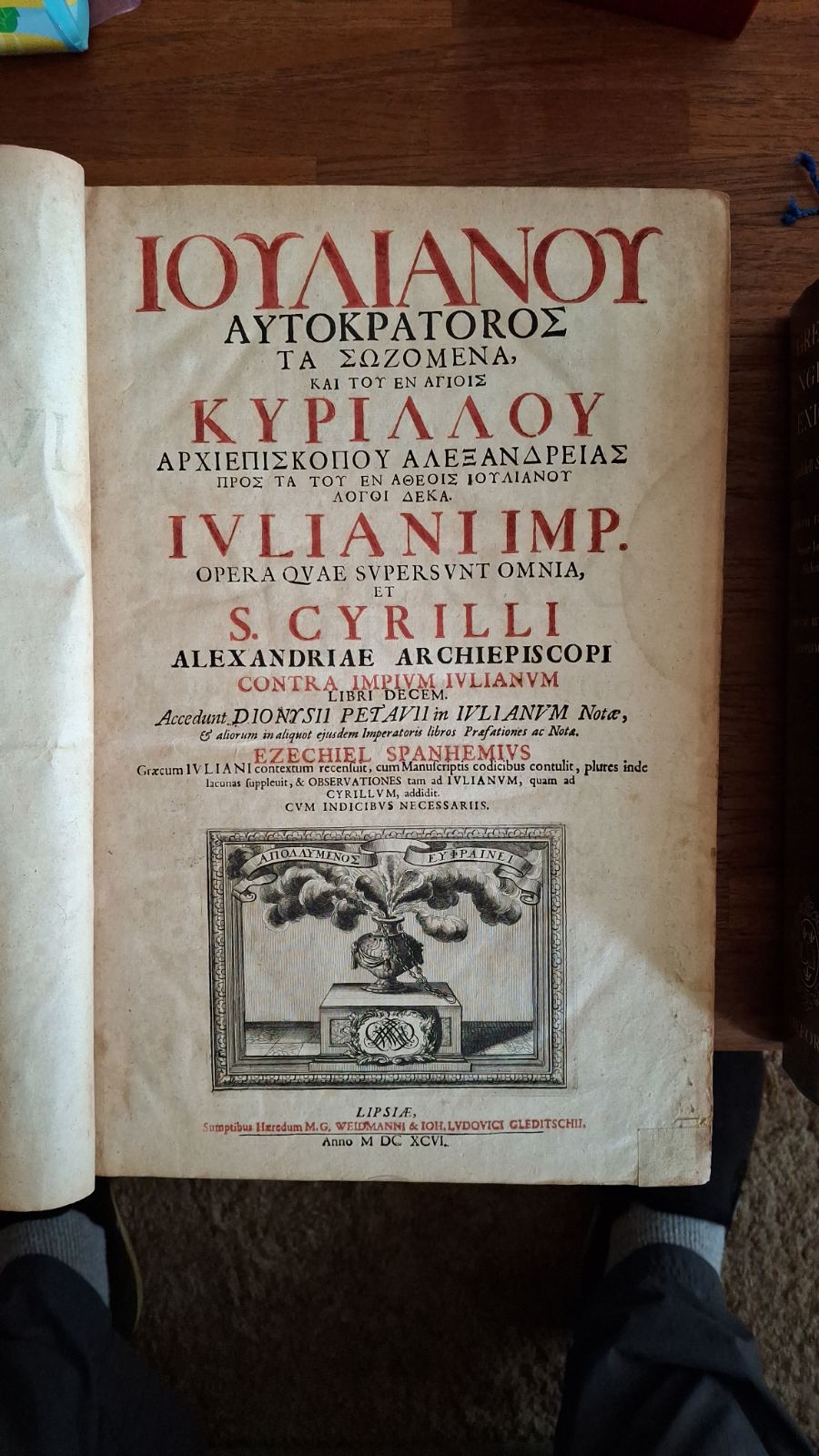

[Lynch’s] big break came in 1996 with Autonomy…. Autonomy’s software, made up of pattern-matching algorithms, was touted as a solution that could help employees abstract meaning from unstructured data, including web pages, email, video, audio and text. These pattern recognition techniques were based on so-called Bayesian inference, a method of statistical inference named after a theorem developed by 18th century statistician Thomas Bayes. Lynch’s luxury yacht, the Bayesian, was named after this mathematical model.[1]

Five other people, including Lynch’s daughter Hannah, were also lost in the disaster.

It would be patently unfair to attribute this terrible event to faith in Bayesian prediction methods. According to the manufacturer of the yacht (who obviously has a bias in this matter), basic safety precautions were not taken in this case, such as securely closing all hatches and lowering the keel to its full length to stabilize the vessel. The results in a (very rare) storm of this intensity were almost certainly predictable; formal Bayesian approaches would not even be required to prepare for them.

But faith in Bayesian methods of prediction, in spheres for which such techniques were either inapplicable or useless, has led to any number of disasters in this century. And many of them involved the use of Bayesian prognostication to predict the future of what are called intersubjective realities.

Intersubjective realities are essentially agreed-upon fictions, such as corporations, the rules that make sports playable, religions, currencies, constitutions, or economic indicators, that have no physical reality in and of themselves, and so rely upon the general agreement of a community for their power and significance.

The results of a poker game might seem to fall into this category, because they depend upon the agreement of a community of players in order to have their effect. But poker is a far more concrete game, with far more easily understood rules, than, say, religion, or even the values of currencies, or company stock shares. Poker was designed specifically to deliver these unambiguous outcomes. It is still possible to cheat at poker, but the advent of camera coverage in casinos has made cheating in high-level tournaments far more difficult and riskier.

Games in general are designed to deliver unambiguous results that are otherwise difficult to find in life. So they are near-ideal spheres for the use of Bayesian prediction. Baseball is one such game. It is probably fair to say that Nate Silver achieved his first worldly success as a Bayesian forecaster in his work for Baseball Prospectus and his development of the PECOTA model for predicting player performance.

But Nate only came to true prominence with his move into political prognostication, with the 2008 elections. His accurate prediction of the winners of 49 out of 50 states in the 2008 presidential election, and then 50 out of 50 in 2012, cemented his status as probably the best known practitioner of the art of Bayesian forecasting in the world.

Sadly, that reputation took a bit of a hit in 2016, when his final prediction was wrong in a number of key large swing states, among them Pennsylvania, Michigan, Florida, North Carolina, and Wisconsin, which among them accounted for 90 of the 270 votes needed for any candidate to win.

Elections (especially ones like the rickety eighteenth-century Rube Goldberg mechanism of the U.S. Electoral College), are also intersubjective realities. They rely on a general agreement on results in order to work. There are physical ballots in many cases, but not all; and even physical ballots can be called into question if the results are close enough (see Florida, hanging chads, 2000). Furthermore, if one side is determined not to accept results they do not like, then the legitimacy of the winner (no matter how unambiguous the result may seem to the winner’s supporters) can be called into doubt (see 2020).

And even when the losers acknowledge that they have lost, the point predictions of even the most conscientious Bayesian forecaster may come under fire by aggrieved believers in his or her prognostications, and the technical explanations for the results varying from those predicted, no matter how legitimate, will likely be scorned by those who have an emotional stake in the outcome.

Hence (I rashly assume) Nate Silver’s departure from fivethirtyeight.com. Despite his best efforts to educate the public about the limitations and error margins inherent in Bayesian forecasting, that public remained certain that Nate was in the oracle business, and failure to perfectly predict winners was not only an error (which Nate would tell them was inevitable), but a violation of trust. And Nate, I think, felt their ire keenly, which is understandable. He had never misrepresented himself. They just heard what they wanted to hear.

In my last article, I spoke of “The River,” the competitive, numbers-focused, betting-obsessed, quantitatively objective mindset, as a sort of cancer that had grown beyond its appropriate sphere to colonize all other areas of human endeavor. Numbers have their place – where the sphere in question is predictable and the consequences of being wrong are survivable. But past data, while it can perfectly predict the full range of outcomes in a poker game, cannot do so for intersubjective realities – like Wall Street.

In 2007, Goldman Sachs had a model of the U.S. mortgage market that relied upon past data. Some sources seem to indicate that that data did not go back to any previous era in which housing prices had declined across the entire country. Whether that caused Goldman to assume that such a thing could never happen, I do not know. But I think it highly likely that similarly flawed assumptions were in fact incorporated into their model.

The hypertrophy of quantitative approaches, including some arcane derivatives imported into finance by former physicists and mathematicians, caused almost everyone involved to believe that they were living in a new era in which uncertainty had been conquered and huge sums of money could be made without taking on concomitant levels of risk. The problem was not a lack of data, nor a lack of mathematical competence. The problem was a lack of imagination.

Very few people actually took the time to imagine the entire house of cards being blown to smithereens. That’s because our entire society is all about what Nate calls “The River.” Quantitative approaches are seen as the ONLY legitimate way to deal with the future, even for ineffable intersubjective realities, and 99 times out of 100, those quantitative approaches use models based on past experience to predict the future. Which is great as long as those exact equations continue to track with the chaotic and unpredictable opinions of masses of humans. But the moment they do not (and that moment is never too long in coming – usually just long enough to draw in a large amount of suckers), KABOOM.

We should teach rigorous imagination in our schools. Instead, Nate’s “River” just floods its banks even more, drowning curricula at Harvard Business School, Stanford, Wharton, you name it, in “Big Data” approaches to the future, with qualitative, imaginative approaches dismissed and sneered at.

But the only way you can prepare yourself for the future is by opening up your mind to the full range of plausible eventualities. And you cannot do that with numbers. ALL DATA IS ABOUT THE PAST, NOT THE FUTURE. The cancer of the River is killing our societal capacity to anticipate.

Someone should have anticipated that storm in Sicily. Doubtless it was just too far down the fat tail of past experience, too far from the center of the bell curve. Assumptions of technical competence were made, assumptions that all plausible outcomes were being prepared for. No one imagined that perhaps a changing climate might throw out a storm of a type never seen before in that location. Maybe there was even a poker game going on that night.

And so the Bayesian went down.

[1] https://www.cnbc.com/2024/08/22/mike-lynch-man-once-dubbed-britains-bill-gates-dies-at-age-59.html#:~:text=Tech-,Mike%20Lynch%2C%20man%20once%20dubbed%20’Britain’s%20Bill,Gates%2C’%20dies%20at%20age%2059&text=Mike%20Lynch%2C%20who%20had%20just,He%20was%2059.