[excerpted from Fatal Certainty]

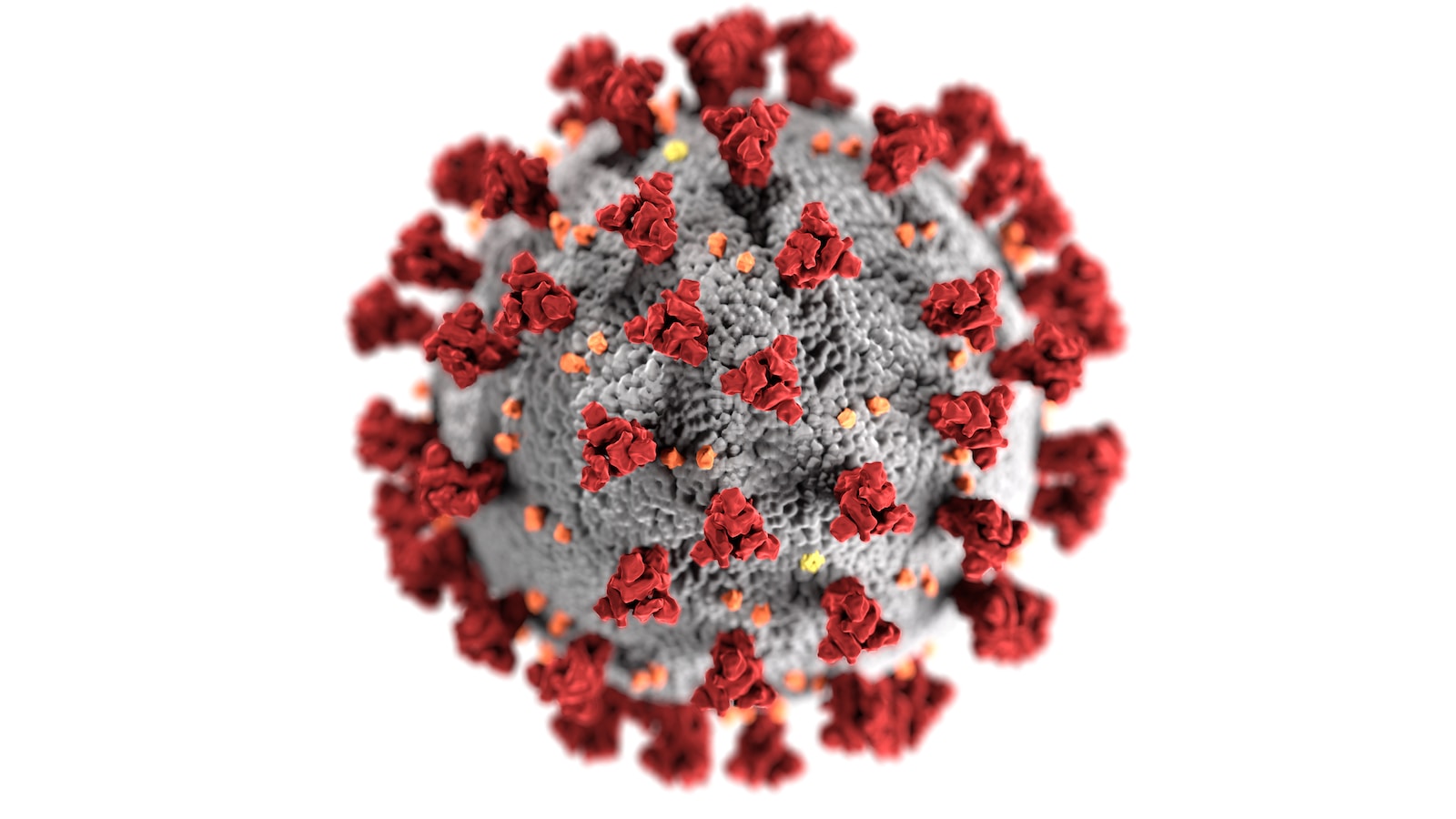

Consider the following passage, in light of the SARS Coronavirus 2 (COVID-19) pandemic of late 2019-present:

…[A] variant of the supposedly beaten SARS corona virus made its way into the United States… At first the new virus was downplayed by public officials. When voters started dying in western port cities, however, “SARS 2” became a hot political issue…. [P]ublic officials who had urged calm and who had insisted that there was nothing to worry about were suddenly in deep political trouble.

As evidence came to light that linked the new virus to China once again, a wave of xenophobia swept across the United States. Incoming international flights were restricted to the handful of airports that had enough space to examine and quarantine large numbers of entrants. Both the Mexican and Canadian borders were subject to heightened surveillance.

…And yet, even with these restrictions, the disease could not be halted. The infrastructure that had been dismantled over the decades might not have been able to contain such an outbreak, but the total lack of such infrastructure now made its spread to pandemic status inevitable. SARS 2 made its way from coastal cities to large interior cities within weeks. After two months, only the most remote areas of the United States had been spared. Deaths were, by international standards, fairly low; just 2% of victims who came down with the disease died in the U.S. Still, this was far beyond the experience of any but the oldest citizens, and it spurred a whole range of changes in the American way of life.

… SARS 2 took a hundred times as many lives as 9/11. Some politicians pointed out that this was still fewer than the number dying from smoking-related illness, and others pointed out that, bad as SARS 2 was, terrorism was still in many ways a deeper threat to Americans. …But SARS 2 was killing people from Key West to Seattle, and from Hawaii to Maine.

Asian Americans were suddenly under…suspicion…. [S]chools emptied for months…. Technology became an invasive force in American society.

Air travel collapsed…. Only a series of loan guarantees backed by the U.S. government got…carriers back into the air, with radically scaled-down schedules. The thought of sharing constantly recycled air with a hundred or more fellow travelers was not acceptable to any but the rashest or most desperate. All “unnecessary” air travel was halted, and teleconferences, so long predicted as the inevitable substitute for travel, finally became an everyday reality.

A “second wave” of infection hit the United States in particular extremely hard.

… Life slowed down; …the standard work week was shrinking…. People lived as much as possible “within the bubble” of their “certified clean” communities…. [I]t was difficult to separate positive solidarity from fear and loathing of outsiders.

…[N]ew medicines, treatment regimens and government action, [seem] to be finally beating back this latest attack. But the outcome… still remains in doubt.

…[M]ost allies overseas, much less enemies, were decrying America’s sudden shift against international institutions and the world order it had spent so much time and effort constructing after World War II.

Global trade, brought to a virtual standstill in the months after the initial outbreak, staggered back to its feet, at far lower levels, with new restrictions on handling and stringent new certification procedures. … [M]illions more died of SARS 2, and from the previous gutting of their public health infrastructures in order to finance military and industrial spending….

Now consider that these words were written in 2003.

Your first reaction may be something along the lines of “That’s eerie; how could someone predict COVID-19 seventeen years ahead of time?”

The short answer is, no one could. The longer answer, as to how premonitions like this one are not only possible, but actually part of our duty, requires something like a book.